The Instacart effect

It’s certainly not for lack of effort, but my assigned “grocery guru,” Dipesh, just can’t find the Ceres Whispers of Summer juice I’ve ordered through the online grocery delivery service Urbery.

Using the phone number I was required to provide when placing my order, Dipesh texts me with the bad news at 9:01 p.m. It has been two hours since online order #1367 was placed; there are just 59 minutes remaining for Urbery to fulfil its promise of delivering groceries to my home, in west end Toronto, within three hours.

That one-litre Tetra Pak of Ceres juice is the lone outstanding product in my 10-item order, which includes staples such as bread and eggs, fresh veggies, packaged meat, toothpaste and ice cream. The list has been carefully assembled for the sole purpose of challenging Dipesh, who is an unwitting, but extremely good-natured, participant in my journalistic experiment. Dipesh has already tried to find the juice at Loblaws, Sobeys and Metro stores downtown. After I reject a handful of suggested alternatives, he says he will make one final effort to track it down, at the Metro store close to my house.

“See you in a bit,” he texts. It is now 9:06 p.m.

Moments later, I’m watching my iPhone, fascinated as an orange dot representing Dipesh’s white Mazda 6 (all of this information has been conveyed to me via an embedded link in a text message generated by Urbery) arrives at the nearby Metro. The dot doesn’t move for five... 10... 13 minutes, and I can picture poor Dipesh roaming the aisles in search of the elusive Ceres juice, perhaps glancing at his watch and cursing the South African juice company’s apparent lack of distribution.

He finally texts again at 9:34 p.m.: no luck. Would I like a substitute or refund? “Refund is fine. Thanks for trying,” I type back. “Will do. See you soon,” he says. It is 9:35 p.m.

Finally, at 9:53 p.m., exactly two hours and 53 minutes after Urbery e-mailed me my confirmation order, a broadly smiling Dipesh is standing at my front door holding a canvas shopping bag filled with groceries. He’s brought two regular kales, he says, because the organic kale I ordered looked a bit wilted. He’s right.

Whether it’s squeezing the Charmin, eyeballing the grapes or sniffing the chicken, grocery shopping has always seemed like an endeavour that takes sensory input. Services such as Urbery, however, require consumers place their trust in a stranger–no small feat. Yet the baguette I ordered is both crispy and soft; the Naturegg Omega Plus eggs are all intact (with a best-before date well within acceptable range); and the ice cream is still frozen.

Best of all, I got it all without ever leaving my house. Maybe this really is the grocery business of the future.

LAUNCHED IN FEBRUARY, BY FORMER SOBEYS CORporate strategy manager Mudit Rawat, Urbery (its name is a mashup of the words “urban” and “grocery”) is part of a new wave of online services aimed at shaking up the grocery business.

Alongside counterparts such as Instacart, Instabuggy and FreshRush, Urbery’s business is built on getting groceries to customers as quickly as possible. To achieve this, it relies on a combination of technology, nimbleness and, perhaps most importantly, a changing customer mindset.

READ: New grocery delivery service sets itself apart with speed

What such services don’t rely on is costly legacy systems such as supplychain infrastructure, warehouses and refrigerated trucks, which eat into profits faster than Cookie Monster scarfing a bag of Nestlé Toll House.

Whereas online grocers such as Grocery Gateway in Toronto and Fresh Direct in NewYork have traditionally promised next day or even same-week delivery, this new wave of services–more tech companies than grocery retailers, really–promise delivery within one to three hours in larger cities.

READ: InstaBuggy delivery service launches in Toronto

Bill Bishop, chief architect with Illinois grocery consultancy Brick Meets Click, believes services such as Instacart and Urbery are changing the very definition of online shopping with delivery. Where the business has traditionally focused on stock-up trips, which represent only about 20% of all grocery trips, one-hour delivery makes it easy for shoppers to fill-in between trips.

“The time aspect of it is a change factor,” he says. “It’s flipping the switch in shoppers’ minds in terms of how they have to approach it. They don’t have to build a 40- or 50-item order. That more spontaneous ‘I want it now’

MANY IN THIS NEW WAVE OF SAMEDAY DELIVERY companies are trying to emulate Instacart, which has exploded into 16 metro areas across the U.S. in just three years, and was valued at US$2 billion in a round of series-C funding earlier this year.

Nilam Ganenthiran, Toronto-based vice-president of business development and strategy at Instacart, says the Canadian grocery shopper now looks much like the American consumer did when the company debuted, in 2012: increasingly comfortable with online ordering, and willing to trust people hired to fulfil a grocery order. While he won’t provide specifics, Ganenthiran says Instacart is poised to launch in Canada later this year or in early 2016.

“I really think Canada’s at a tipping point, because the consumer need is no less prevalent,” he says. “In fact, it’s potentially greater, especially in winter months. We are extremely bullish on Canada.”

University of Waterloo graduate Apoorva Mehta launched Instacart, in San Francisco, with zero marketing or PR. Within a year, says Ganenthiran, it was being used by 1.5% of San Francisco households. This despite the fact that he admits its initial selection and price “wasn’t great.”

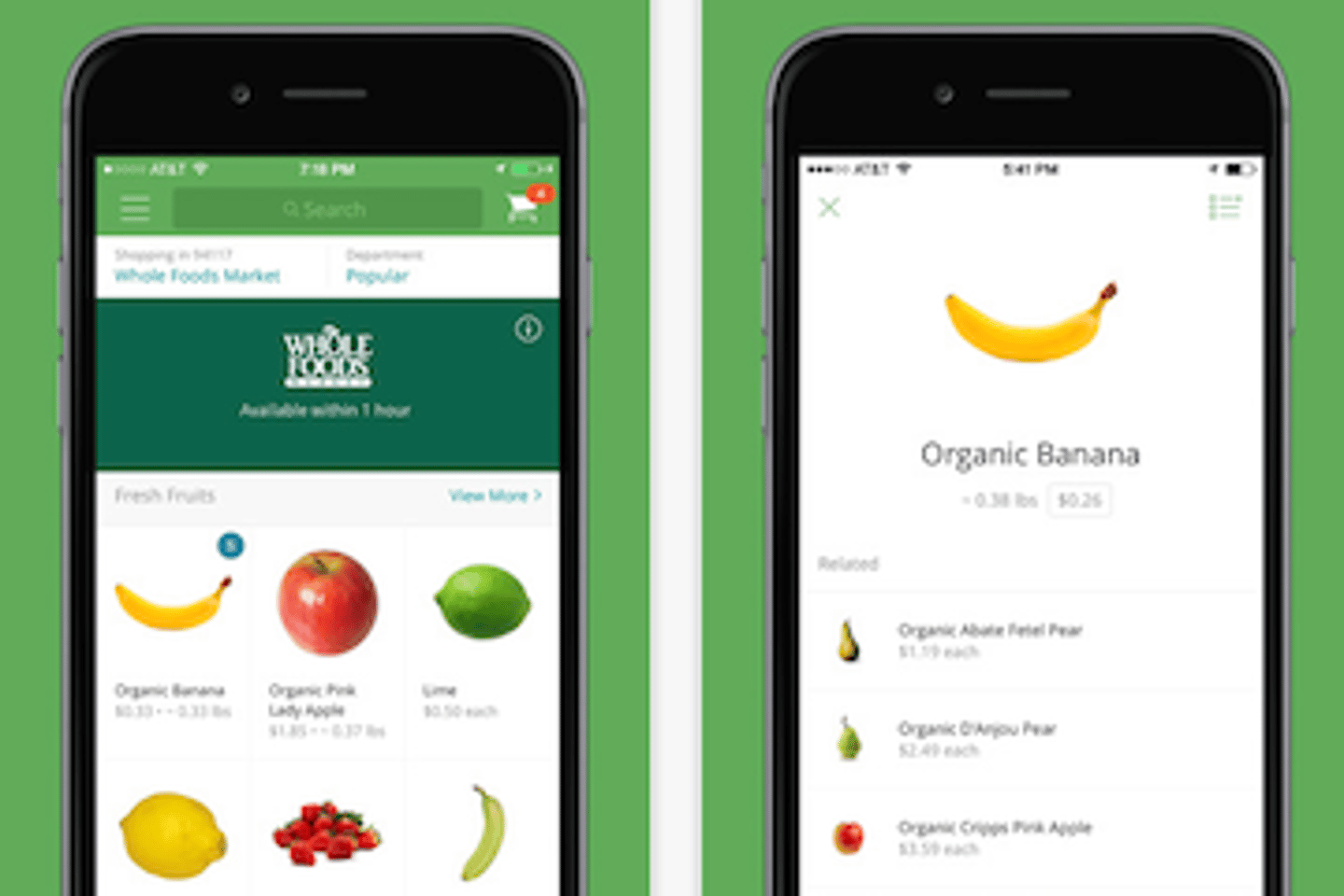

READ: Whole Foods and Instacart marriage proves “fruit-full”

“What it did have was the fact it was solving a very real pain point in the hearts and minds of consumers,” says Ganenthiran. “It was giving customers two hours of their life back for a pretty low cost.” That cost can come two ways: some delivery companies slightly inflate the price for grocery items (as Urbery does, plus a delivery fee) and/or charge delivery fees from $3.99 to $9.99 (as in Instacart’s case).

Keith Anderson, VP of strategy and insight with ecommerce expert Profitero, says additional fees explain why the earliest adopters of these services tend to be higher-income households that value time over money and will pay a modest premium for convenience.

As Instacart’s U.S. rollout has proven, however, it’s difficult to make ironclad predictions about who these services will appeal to most. Instacart expected to cater to condo-dwelling urban millennials, and that was the case. At first, anyway.

Today, Ganenthiran says young dual-income families with Johnny in soccer and Suzy in ballet comprise about one-third of its customers. They tend to order baskets three to four times the size of the average Instacart order, with Ganenthiran estimating the service fulfils one in every two to three of this segment’s stock-up grocery orders.

READ: Instacart changes its personal shoppers’ status

Rawat says Urbery has experienced a similar phenomenon. “

Both services cater to multiple customer segments. Instacart also delivers to small businesses, some of which often spend between $800 and $1,200 on each shopping occasion, as well as a group that Ganenthiran calls a “forgotten constituency:” the elderly. “It’s a really unique group because nobody talks about them in relation to e-commerce, but they’re huge and growing,” he says.

SAMEDAY DELIVERY SERVICES–ALONG with click-and-collect services offered by established grocers such as Loblaw– are helping to create a wave of new consumer spending in grocery e-commerce that Stewart Samuel, senior business analyst with global grocery and food research firm IGD, believes could push Canada’s online grocery industry to $800 million by 2020. While that is a fraction of countries such as the U.K. (US$15 billion in 2015), France (US$9 billion) and global leader China (US$41 billion, but largely population driven), it is trending upwards.

“We know the direction the market’s going

in, but what’s difficult to judge is the speed and pace,” says Samuel. “We don’t know how quickly the retailers will roll it out. We haven’t got a clear picture on consumer acceptance.”

When Instacart does decide to hop into Canada, it will face several homegrown rivals. Besides Urbery, there is Instabuggy, which started in April promising one-hour delivery to homes and businesses in downtown Toronto from stores such as FreshCo.

READ: Overwaitea pilots online shopping program

Cartly, a Brampton, Ont.-based startup, aims to offer delivery of ethnic goods. Cartly hopes to team up with Toronto-area ethnic supermarkets, which are less likely to have their own online businesses, says CEO, Praveen Korukonda.

In Vancouver, 23-year-old Ali Javon is launch- ing FreshRush, which promises to deliver from Safeway, Whole Foods, Costco and other stores in an hour.

While all of these services share DNA, they also each have a unique selling proposition designed to differentiate them in a rapidly grow- ing field. When Instacart enters a new market, for example, it does so through partnerships with existing retailers, including Costco and Whole Foods.

Instacart has a dual revenue stream, generating income from both delivery fees and a standardized fee structure that sees retail partners pay anunspecified amount on every order. Ganenthiran says working with grocers allows Instacart to offload services such as merchandising and pricing to its retail partners, which in turn lowers the end cost for customers.

It is an approach that enables Instacart to ramp up quickly, achieving the required scale so crucial to thriving in an industry where profit margins are already Olsen-twin thin. “Just like the industry we’re serving, it’s a low-margin, high-volume business,” says Ganenthiran.

READ: New app locates local food

He says Instacart’s Canadian rollout will likely differ from the U.S. because three major chains–Loblaw, Sobeys and Metro–essentially control the entire industry. “The level of sophistication in Canada is really quite high,” he says. “Retailers understand

Urbery’s model, meanwhile, sometimes requires personal shoppers such as Dipesh to visit multiple stores to fulfil an order. “We allow people to say, ‘I really want Loblaw’s PC product X, and then I want you to go to Sobeys and get me that Jamie Oliver pasta,’” says Rawat. “We can do that.”

Combined with the roughly 15% mark-up Urbery builds into prices, and the $5.99 delivery charge for orders between $35 to $55 (orders less than $35 are $9.99; orders more than $65 free), my grocery shop cost me $57. That’s about $15 more than I would have spent at my local grocery store. Despite my modest journalist’s salary, I deemed it an acceptable trade-off.

READ: Doing Torontonians a Favour

After each delivery, Urbery sends a text asking customers to rate the service on key factors such as timeliness and accuracy of the delivery, and qual- ity of the food selected. Rawat says the company is currently averaging a score of 4.8 out of five.

The company’s focus at launch was on getting customers their order quickly, but that has shifted somewhat over time to place a greater emphasis on quality. “I don’t think many companies do that well, and we’ve tried to make that core to our business,” he says. Somewhere on the streets of Toronto, Dipesh is working tirelessly to fulfil that brand promise.