Uncertainty surrounding tariffs remains. What can grocers do?

With U.S. President Donald Trump set to impose more levies on Canadian goods beginning April 2, a great deal of uncertainty remains. Tariffs threaten to disrupt established supply chains, put pressure on economic growth, hinder innovation and drive declines in consumer confidence.

We recently spoke with Fraser Johnson, the Leenders Supply Chain Management Association Chair at the Ivey Business School, about this and more. The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

How should the Canadian grocery industry adjust to a prolonged period of tariff uncertainty?

Well, this is part of the problem. Things like steel, aluminum and oil, potentially, affects packaging. So, containers, canned foods, beverage containers, plastic containers—a lot of that stuff tends to go back and forth across the border. The steel may come from Canada, be processed in the U.S. and then shipped back into Canada to be used in a manufacturing process. One of the things people need to keep an eye on is not just the raw inputs in terms of food, but also the associated materials. And what tends to get lost here is the effect on the exchange rate. Today, the Canadian dollar is [worth] a little over [U.S.] 70 cents. What that obviously does is makes Canadian goods more attractive to Americans, but makes imports—the fruits and vegetables and other products coming from the U.S.—more expensive. That’s not a tariff, but it is an effect of the tariffs. The reason the Canadian dollar has been devalued is that threat of tariffs and the potential effect on the Canadian economy and the effect on our interest rates relative to the U.S.

READ: FHCP’s Michael Graydon on tariffs and the path ahead for Canada’s food sector

How can grocers deal with potential disruptions to the supply chain?

We talked about the effect of the exchange rate. So, hedging—using the futures markets to minimize the risk in terms of further devaluation of the Canadian dollar—would be one way of protecting yourself. A lot of prices for food are, ultimately, set in U.S. dollars. So, I think looking at the exchange rate risk is part of it and looking for alternative sources to supply. But these things take time, and they have a cost associated with them. And it’s hard to make long-term commitments for a short-term problem so, to what extent do you say, “Well, we’re going to tinker around the edges as opposed to making major structural changes”? You’ve got this period of uncertainty and I think a lot of businesses may just decide to wait it out, adjust prices and make strategic purchases where they can.

What risks are involved when shifting production to another country or switching suppliers?

There's significant risks in terms of quality. If I'm looking for food products from different suppliers in Southeast Asia, Mexico or South America, for example, my consumers may have preferences for particular brands and so it becomes difficult.

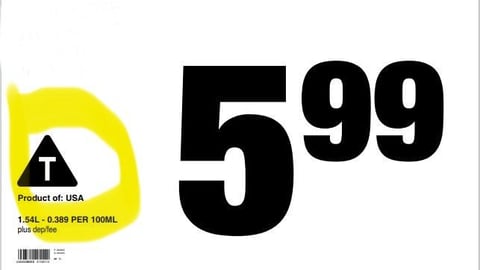

READ: ‘Look for the Leaf’ campaign puts on a united front

In Canada, it takes a lot of investigation for consumers and for grocers to be able to tease where the product is made. You've got the “Product of Canada” claim and the “Made in Canada” claim. I was on Sobeys’ app last night and, sure enough, there's a red maple leaf highlighting items that are products of Canada to make it easier for consumers. For some of the larger chains that have the capabilities of being able to do that and the IT systems to support it, that can be an advantage because to a certain extent consumers are prepared in some cases to pay more to buy Canadian. But, the other part is that with the food inflation we've had over the last three or four years, a lot of consumers are just trying to make ends meet. It's nice to say, “I'm going to buy Canadian.” But, if I have to pay 5% more, 10% more, a lot of people from a very practical standpoint can't afford to do that.

During a trade war, can Canadian producers fill gaps in the supply chain?

Well, I think your readers need to look at options. Importing goods directly from Mexico, for example, becomes more expensive because of the transportation costs. If you’re importing avocados and bananas and pineapples, there’s only certain parts of the world where you can get that product. But, there’s a disproportional impact on small-and-medium-sized businesses here. Walmart and Costco have sophisticated supply chain machines that can adapt to these changes and optimize their cost solutions. If I’m an independent grocer in Toronto or Calgary or Vancouver, I’m severely limited in terms of what my options are and the length of time it takes.

Tariffs, no tariffs. What lessons can grocers take away from this?

I think depending upon the size of the organization, having a war room and dedicated resources to monitor what’s going on so you understand what parts of your businesses are being affected [is beneficial]. So, it involves sourcing, it involves logistics and it involves your operations. Rather than just reacting, I think there are opportunities, even for a small organization, to be proactive in terms of monitoring what’s happening and collecting data. I think from an industry standpoint, lobbying the government at all levels is important. And one of the things we haven’t talked about is interprovincial trade barriers. To me, that’s a completely independent issue from tariffs, but it’s under the spotlight again. I’m not sure, specifically, how it affects the grocery industry, but I’m sure it does because there’s a lot of east-west movement of food products in Canada.

READ: Carney demands respect from U.S. as Trump doubles steel tariff

Is there a silver lining?

It may force companies to make changes and examine alternatives that were uncomfortable before in terms of sourcing options and logistics. At the end of the day, they may find alternative sources of supply in different parts of the world, but supply chains in North America tend to be pretty well-oiled machines with a lot of the dominant players. I’m hoping cooler heads will prevail … I thought the U.S. president would have other things to worry about than the tariffs on Canada and calling our [former] Prime Minister "Governor Trudeau"—apparently he doesn’t. So, I’m hoping the momentum will shift to other important policy issues. But, let’s wait and see.

This article was first published in Canadian Grocer’s March/April 2025 issue.