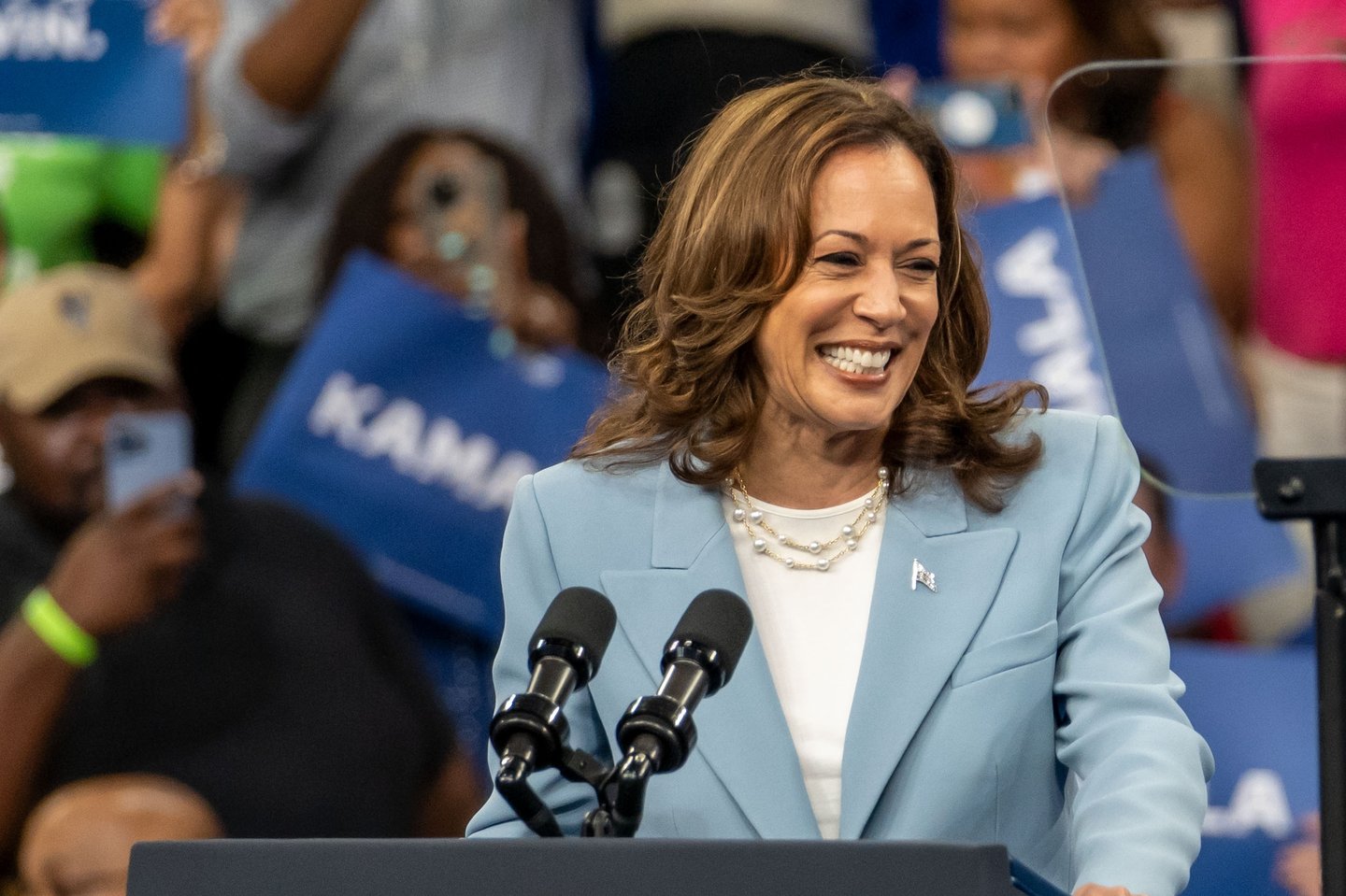

Hope in Harris Canada’s agri-food sector’s safer bet

As Canadians anticipate the American election on November 5, many are asking: who is the best President for Canada’s agri-food sector and food security? The answer isn’t straightforward. However, a Harris presidency may bring challenges but with less volatility and theatrics than a second Trump term.

Regardless of the outcome, provided Congress continues to check the power of the White House, global trade may shift towards a more protectionist stance, marked by increased tariffs. This shift would likely drive inflation higher, affecting prices across the board, including food, and leading to increased interest rates. In other words, the next presidency could make the world a more expensive place for everyone, with food prices taking a hit.

Harris, who opposed the USMCA (formerly NAFTA 2.0) for not going far enough on environmental issues, could push Canada and Mexico into new rounds of negotiations for what could become "USMCA 2.0." Trump, too, has signaled intentions to renegotiate the USMCA, likely aiming for increased access to Canada's dairy industry—a sector he has fixated on in the past. Yet, America’s primary concern remains Mexico’s economic role, which has substantial ripple effects on the American economy. Canada’s leaders must remember: while both countries depend on each other, Canada relies on the U.S. market more than it does on ours.

Trump, like Harris, also promises tariffs, but his approach would likely trigger trade conflicts, especially with China. Meanwhile, China has expanded its alliances, particularly with BRICS nations. Recent discussions among BRICS leaders, hosted by Vladimir Putin, emphasized agri-food trade and even touched on a common currency. China has begun purchasing soy from Russia, a relatively minor player compared to the U.S., signaling a pivot toward alternative trading partners. While the U.S.-led economic sphere, including Canada, adopts a protectionist stance, BRICS nations are leaning into trade openness and partnership—a stark geopolitical divide.

READ: Budget blues and our food future

In Washington, rumors suggest that a Trump administration might involve Robert F. Kennedy in agriculture, potentially even as Secretary of Agriculture. His vision emphasizes healthier, domestically-produced food, smaller farms, and environmental sustainability—a notable shift from Trump’s first term, which leaned toward provocation rather than policy direction. Trump’s second term would likely bring different players and a more flamboyant approach, but Canada’s agri-food sector may have little appetite for that unpredictability.

Domestically, Canada is grappling with Bill C-282, now in its second reading in the Senate. The bill aims to protect Canada’s supply-managed sectors, like dairy, from foreign competition, but it covers less than 1% of our economy. If enacted, C-282 would set a global precedent: no trade-reliant country has ever legislated the protection of an economic sector in advance of future trade negotiations. By enshrining protectionism into law, C-282 could weaken Canada’s stance in future trade negotiations, especially with the U.S., sending a signal of closed-door protectionism just as global trade tensions are rising. Japan’s rice protections offer a precedent, but Japan doesn’t hold Canada’s role in feeding the world. Unless a Canadian election intervenes, Bill C-282 may soon become law—a precarious position when facing a more protectionist U.S.

In essence, the next American presidency will impact Canada’s food sector, whether through steady, policy-oriented approaches under Harris or through Trump’s unpredictability. Harris might bring a more serious, seminar-like approach to policy, which Canada arguably needs. Trump’s style, in contrast, is like watching an unscripted game show—exhausting and volatile. Canada’s agri-food sector may well have had its fill of that sort of drama.