The push for cage-free eggs is on. Will it help your sales?

How do Canadians like their eggs? More companies are banking on them preferring eggs from hens who don’t spend their lives crammed in cages the size of a piece of paper. Kraft Heinz and General Mills recently committed to using only cage-free eggs in their products within the next decade. Tim Hortons, Burger King, McDonald’s and Starbucks have done the same. A&W aims to go cage-free in two years. But will attention from Ronald McDonald and the A&W guy turn cage-free eggs into surefire sellers at the supermarket? Let’s take a crack at an answer.

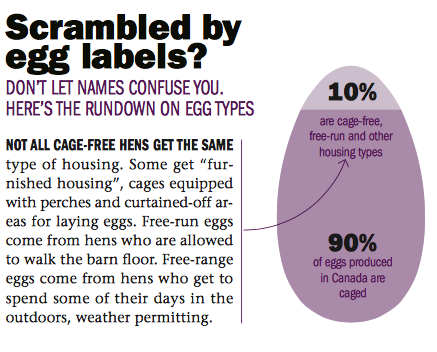

Many grocers stock cage-free eggs, and a few go further to carry free-range eggs. (Don’t know the difference? Read “Scrambled by egg labels?” below.) But several retailers Canadian Grocer spoke with say they have not seen any uptake. Price is likely the deterrent. Cage-free eggs sell for about $1.50 more per carton than conventional eggs.

Some stores do report sunny-side-up sales. Take the Country Grocer, in Victoria. Brian Swaren, dairy manager, says demand for cage-free eggs has more than doubled in the last six months, even with a premium price. “Consumers know what they want, and they’re willing to spend the money on eating well,” he says. “We’re ordering a few extra cases a week and giving

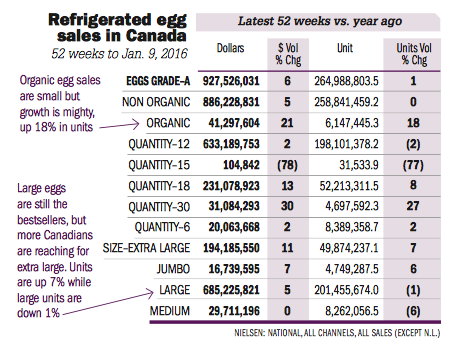

Burnbrae Farms, headquartered in Lyn, Ont., was among the first to introduce commercial-scale free-run (or cage-free) hen housing in Canada, 15 years ago. Its president, Margaret Hudson, says demand has steadily risen since. But eggs from so-called “alternative housing” types still make up only a small percentage of the overall fresh-egg category.

According to Egg Farmers of Canada, which manages the country’s egg supply, about 90% of current egg production comes from conventional, or caged, housing. Egg Farmers is aiming for a 50/50 mix of conventional and alternative in the next eight years, and up to 85% cage-free in 15 years. Ontario egg farmer Roger Pelissero, a member of Egg Farmers’ national board, expects cage-free’s uptake to vary across the country. “Maybe in rural Ontario we won’t sell a lot of cage-free, but in B.C. we will,” he says.

Catching consumers’ eyes will require work. “Since we’ve been in the business, the industry has evolved from essentially one kind of egg produced one way, to now a wide variety of eggs,” says Hudson. But when shoppers open the fridge door in stores, many likely still only think, I need eggs, not, What kind of eggs should I buy?

To help, Burnbrae is in the middle of a major packaging overhaul that Hudson says will make clear the options and benefits of different eggs. In-store signs are almost nonexistent in the category at the moment, she notes, and eggs have long been promoted as a commodity item. But there’s a chance for retailers to trade consumers up to value-added options. “