Generation Next Thinking: Where are grocers in the war on food waste?

Nothing sums up the food waste crisis like this popular meme making the rounds: “Almost left the grocery store without buying a bag of spring mix to throw, unopened, into the garbage in two weeks.” It’s funny because it’s relatable—we’re all guilty of tossing food into our shopping carts, only to find it perishing in the crisper weeks later. However, the statistics on food waste show the issue is no laughing matter.

New research from the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) suggests 17% of total global food production may end up being wasted. UNEP’s “Food Waste Index Report 2021” estimates food waste from households, retailers and foodservice totals 931 million tons each year. The biggest culprits are consumers: nearly 61% of food waste occurs at the household level, while 26% comes from foodservice and 13% comes from retail.

Research from the Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC) shows where food is wasted in North America from farm to fork. Of the 168 million tons of food lost or wasted every year, pre-harvest accounts for 49 million tons, post-harvest adds up to 16 million tons, and processing accounts for 20 million tons. Distribution, retail and foodservice add 15 million tons, and finally, consumers pile on 67 million tons a year.

All that waste takes a huge toll on the environment—and it’s not just about the methane emissions from rotting produce in landfills. “Along with this food that is being wasted, we are also wasting all the resources that went to producing this food,” said Armando Yáñez, head of the Green Growth unit at CEC, in a recent webinar on food loss and waste. That includes wasted water (enough to fill seven million Olympic-sized swimming pools), wasted energy (enough to power 274 million homes), and 193 million tons of greenhouse gas emissions that occur along the supply chain, from food production to waste disposal.

Then there’s the price tag. Research from Value Chain Management International (VCMI), in partnership with Second Harvest, estimates that the value of avoidable food loss and waste in Canada equates to $49.5 billion per year. (Avoidable food loss and waste includes things like bruised apples that don’t get sold, as opposed to unavoidable food loss and waste, meaning byproducts such as peelings and animal bones.) Global estimates peg the cost at between US$940 billion and US$1.2 trillion.

While food waste is a big problem, it’s not a new one. However, the food industry’s progress in tackling the issue is difficult to gauge. “There has been some progress, but the progress may not have been as great as some published figures suggest,” says Martin Gooch, CEO of VCMI. “The reason is a decent number of businesses have changed how they report food loss and waste—it’s not necessarily that the amount of waste has gone down significantly.”

One example is the Food Loss and Waste protocol, a global accounting and reporting standard that launched in 2016. Led by the World Resources Institute, the FLW Standard (as it is known) enables companies, countries, cities and others to quantify and report on food loss and waste so they can create targeted reduction strategies.

The FLW Standard highlights 10 final destinations for food loss and waste such as animal feed, anaerobic digestion, composting and landfill. However, not all destinations are considered to be food loss and waste, since some extract value from the material after it leaves the food supply chain.

That’s a concern for Denise Philippe, a senior policy advisor at National Zero Waste Council of Metro Vancouver. “Part of the problem with the protocol is that you could send your food waste to an anaerobic digester or a composter and that would not be considered waste,” she says. “From the Council’s perspective, if it’s food that is not going to feed people or feed animals, it’s waste.”

Like Gooch, though, Philippe believes some progress is being made, particularly around awareness. “The progress has been that people realize [food loss and waste] is an issue, and that we are suffering economic losses as a result of a system that is inefficient in terms of getting food from farm to fork,” she says. With that acknowledgement, she adds, organizations along the food chain are making efforts to tackle food loss and waste.

While retailers are relatively small contributors to food waste, they have a critical role to play in helping to reduce it—in their own operations, in their suppliers’ operations, and in consumers’ homes. Here’s a look at some of the ways grocers can step up efforts to reduce food waste:

Build more collaborative relationships

A lack of communication and collaboration, both within a retail business and with suppliers, is one of the root causes of food waste, according to VCMI. In its “Avoidable Food Waste: Technical Report,” VCMI explains there is sometimes an unwillingness in the grocery industry to share data, plan and execute collaboratively that, in turn, leads to food waste.

Gooch gives the example of retailers that operate in silos. “Let’s say the logistics side of the business is being incentivized to minimize transport costs,” he says. “They will make sure that trucks are full, even though a portion of the products on those trucks aren’t required.”

On the supplier side, Gooch believes a grocery code of conduct will help reduce food waste as it will lead to better relationships between retailers and manufacturers. “[A code of conduct] makes people accountable. Accountability enables you to build increased trust and grow margins because there is an incentive to share information,” says Gooch.

Better relationships can also lead to more effective procurement strategies, which is another avenue to reduce food waste. “Too often, companies are tied to their procurement strategies and they become an albatross,” says Philippe. She advises retailers to set up procurement strategies with processors, manufacturers and even farmers that allow for a greater level of nimbleness. “It takes work, and there are all kinds of challenges around it, but it’s worthwhile,” she says.

Encourage suppliers to fight food waste

Grocers can also encourage suppliers to reduce food loss and waste in their own operations. “As buyers, there is an incredible opportunity for retailers to influence that supply chain,” says Cher Mereweather, president and CEO of Provision Coalition, which works with food and beverage manufacturers to integrate sustainability into their business models.

By influence, Mereweather means retailers can communicate that loss and waste is important to them and that they want to buy from suppliers that have a handle on the issue. “It’s not about creating more administrative burden with scorecards and questionnaires, but asking their vendors questions,” says Mereweather. “Are you reducing your food waste? Are you monitoring, measuring it and tracking it? And if you’re not, are you open to doing training to help you get a handle on it?”

Sobeys is one major retailer that supports its suppliers with their food waste reduction efforts. In April, Provision Coalition hosted a virtual pitch competition with 14 Ontario-based suppliers that took part in Sobeys’ R-Purpose MICRO, a 12-week intensive program to help food and beverage start-ups “accelerate their growth by becoming more purpose-driven, sustainable and circular.” Mereweather says 100% of the companies in the first graduating cohort are reducing food waste because they implemented plans created during the program.

One example is Abokichi, which makes Japanese-inspired miso condiments. In 2020, Abokichi expanded its product line with an instant miso soup product that’s “upcycled,” meaning made with ingredients that would otherwise go to waste. The miso soup contains a sake-brewing byproduct called sakekasu, resulting in the diversion of 2.3 tons of food waste in 2020.

National Zero Waste Council’s Philippe says there’s a big opportunity for retailers to work with their partners on innovative and creative ways of rethinking the supply chain. Given the challenges of global supply chains, she says re-localizing Canada’s food supply will become increasingly important. “Part of that is rethinking and redefining what are edible food items,” she says. “For example, if we grow potatoes here, let’s not waste the potato skins. All kinds of cool, funky things can be done with them.”

Go high-tech

Technology can be a powerful ally in the fight against food waste. For example, Toronto-based Flashfood is a mobile platform that works with grocers to divert food nearing its best-before date from landfill by offering it at reduced prices. The app allows users to buy a variety of food including meat, produce, bakery items, dairy products and non-perishable food items. In the app, users can select a store, browse items and pay for their order through the app. Items are then ready for in-store pickup in a designated Flashfood zone. The company, founded in 2016, now operates in more than 450 grocery locations throughout Canada, Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. To date, Flashfood has diverted more than five million pounds of food.

Ahold Delhaize is one grocery company using Flashfood; it highlighted its food waste reduction efforts at the recent CEC webinar. The company introduced Flashfood in 2020 at select Giant and Martin’s locations in the United States and later expanded the partnership. “In our 12-week pilot alone, well over 11,000 shoppers took advantage of great deals on Flashfood and we successfully diverted thousands of pounds of food from landfill,” said Christine Gallagher, manager of environmental sustainability at Ahold Delhaize.

Going high-tech to curb food waste doesn’t just mean all things mobile. Ahold Delhaize is piloting a technology called Apeel from California-based Apeel Sciences. It uses materials that exist in the seeds and pulp of fruits and vegetables to create a protective coating that seals moisture in and keeps oxygen out. According to Apeel, produce stays fresh longer since water loss and oxidation causes spoilage.

Donate and repurpose edible food

While retailers can make valiant efforts to reduce food waste, it’s nearly impossible to totally eliminate it. “There is always going to be a certain amount of waste,” says VCMI’s Gooch. That’s where donating safe, edible food comes in. “And if you can’t donate it, how do you valorize it, or get some value from it.”

That’s another approach Empire/Sobeys is taking, as part of its goal to prevent and reduce its food waste by 50% by 2025. The grocer recently launched a national partnership with Second Harvest to adopt its FoodRescue.ca platform, which allows retailers to donate any type of surplus food directly to approved charities and non-profit organizations at any time. Retailers outline what items they have available and the donation is matched to appropriate local organizations, which then receive notifications.

“We are bringing the Second Harvest Food Rescue app to all our stores across our various banners over the next 16 to 18 months,” says Eli Browne, director of corporate sustainability at Sobeys. “Through this partnership, we’ll be able to divert up to 31 million pounds of food from going to composting or landfilling, and instead [it will be] feeding people.”

On the repurposing front, Sobeys is working with Outcast Foods to minimize food waste by upcycling unused fruits and vegetables from a Sobeys distribution centre in Nova Scotia and select stores in the province. Outcast uses a process to dry fruits and vegetables destined for landfills, giving them an extra three years of shelf life. The ingredients are then used in Outcast’s Plant Strong Protein products, which are sold at Sobeys and other retailers.

Turner Wyatt, co-founder and CEO of Denver-based Upcycled Food Association, notes that a recent study published in the journal Food and Nutrition Sciences found that just 10% of consumers are familiar with upcycled food products. However, once educated about upcycled foods, 80% said they would seek out those products.

“Our No. 1 goal is to educate as many millions of people as we can around the world about upcycled food,” he says. “If more people know what it is, demand will grow naturally.” And, he adds, the place where consumers are primed to find out about new concepts is the grocery store. “Even though retailers waste the least amount of food by entity type, they have the most responsibility because they have the greatest access to consumers. And consumers are the most important entity in the equation.”

Help consumers reduce household food waste

To understand how grocers can help consumers reduce food waste at home, they first have to understand the root causes. Joanne Gauci, a senior policy advisor at National Zero Waste Council of Metro Vancouver, says there are three key areas: consumers are not planning well and buying too much food; they’re not storing it correctly; and they don’t know what to do with leftovers.

Research from the National Zero Waste Council found that 63% of the food Canadians throw away or compost could have been eaten. For the average household, that costs $1,100 per year. The most commonly wasted foods are vegetables, fruits and leftovers. The good news is that 94% of Canadians are motivated to reduce their household’s avoidable food waste, according to a 2020 survey by the Council.

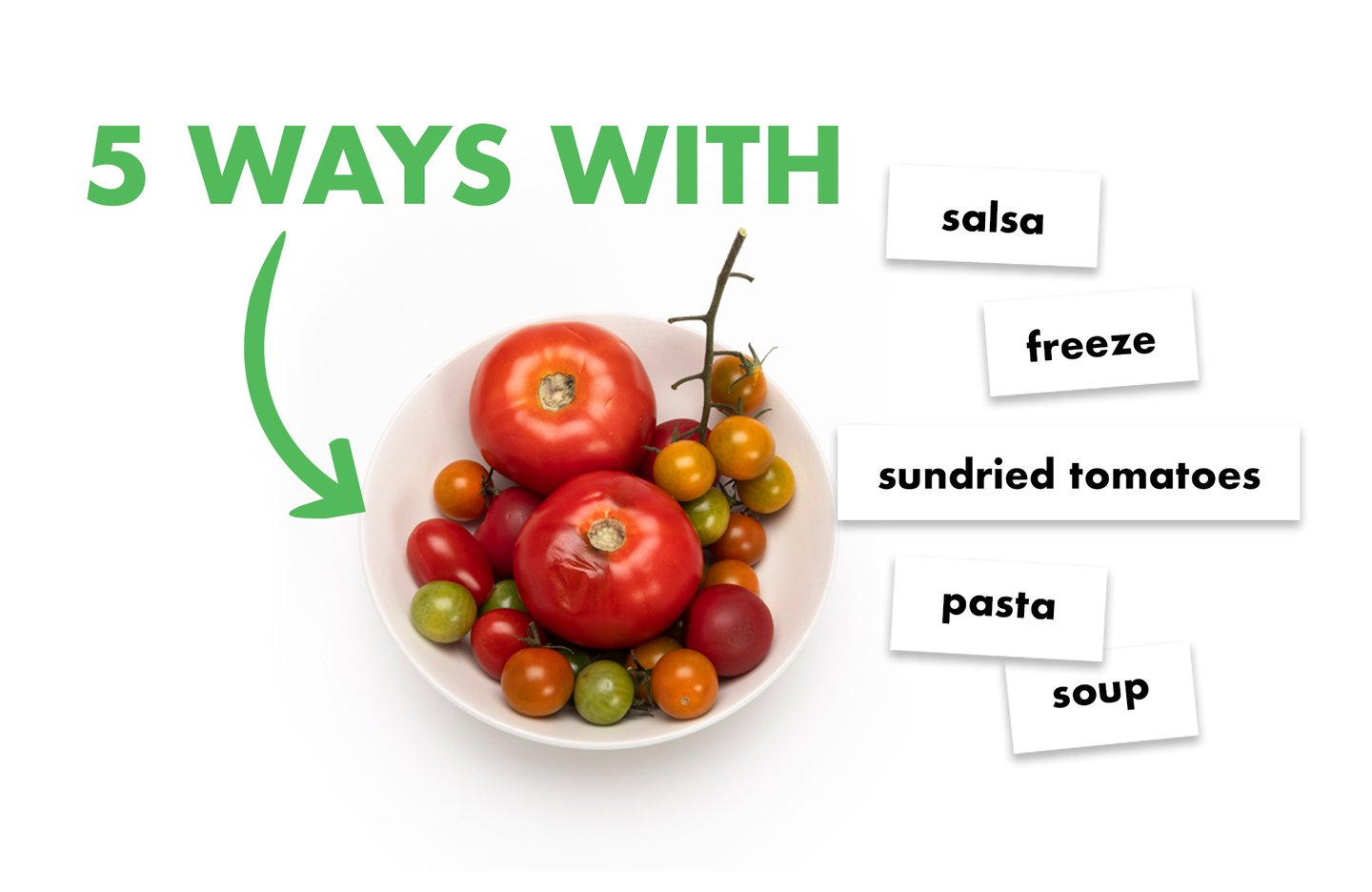

To help Canadians reduce food waste, the National Zero Waste Council’s ongoing “Love Food Hate Waste” campaign provides tips on food storage, meal planning and smarter shopping habits, as well as recipes. This month, the Council is launching its “5 Ways With” campaign that gives consumers tips on what to do with the most commonly wasted food products. For example, the campaign will highlight “5 ways with broccoli stalks” and “5 ways with stale bread.” “It’s intended to be a source of inspiration for consumers and the campaign will feature influencers who also share their tips and insights,” says Gauci. The Council has 11 campaign partners, including two grocery partners: Sobeys and Walmart.

Provision Coalition’s Mereweather agrees the industry has an important role to play in supporting national campaigns like those from National Zero Waste Council. “If retailers and food companies start communicating the importance of food waste prevention at home, then we have consistent messaging.”

Certainly, for everyone along the chain—from manufacturers to retailers to consumers—the message to take food waste seriously should be loud and clear.

Generation Next Thinking is an ongoing series that explores cutting-edge topics that will help grocers gain the knowledge they need to tackle the future of this rapidly-changing industry.