Convenience over cost: Food delivery apps redefining eating in Canada

Do you use platforms such as UberEats or DoorDash to order meals at the office or at home? If so, you’re not alone. The growth of these applications has been significant in recent years, though it varies widely across regions and generations.

According to a survey conducted in late August by Dalhousie University’s Agri-Food Analytics Lab, in partnership with Caddle, 27.4% of Canadians now order through these platforms more than once a month. That’s a clear increase from 2020, when only 20% of Canadians did so on a regular basis. In 2020, one in five Canadians used food delivery apps regularly. Today, it’s one in four.

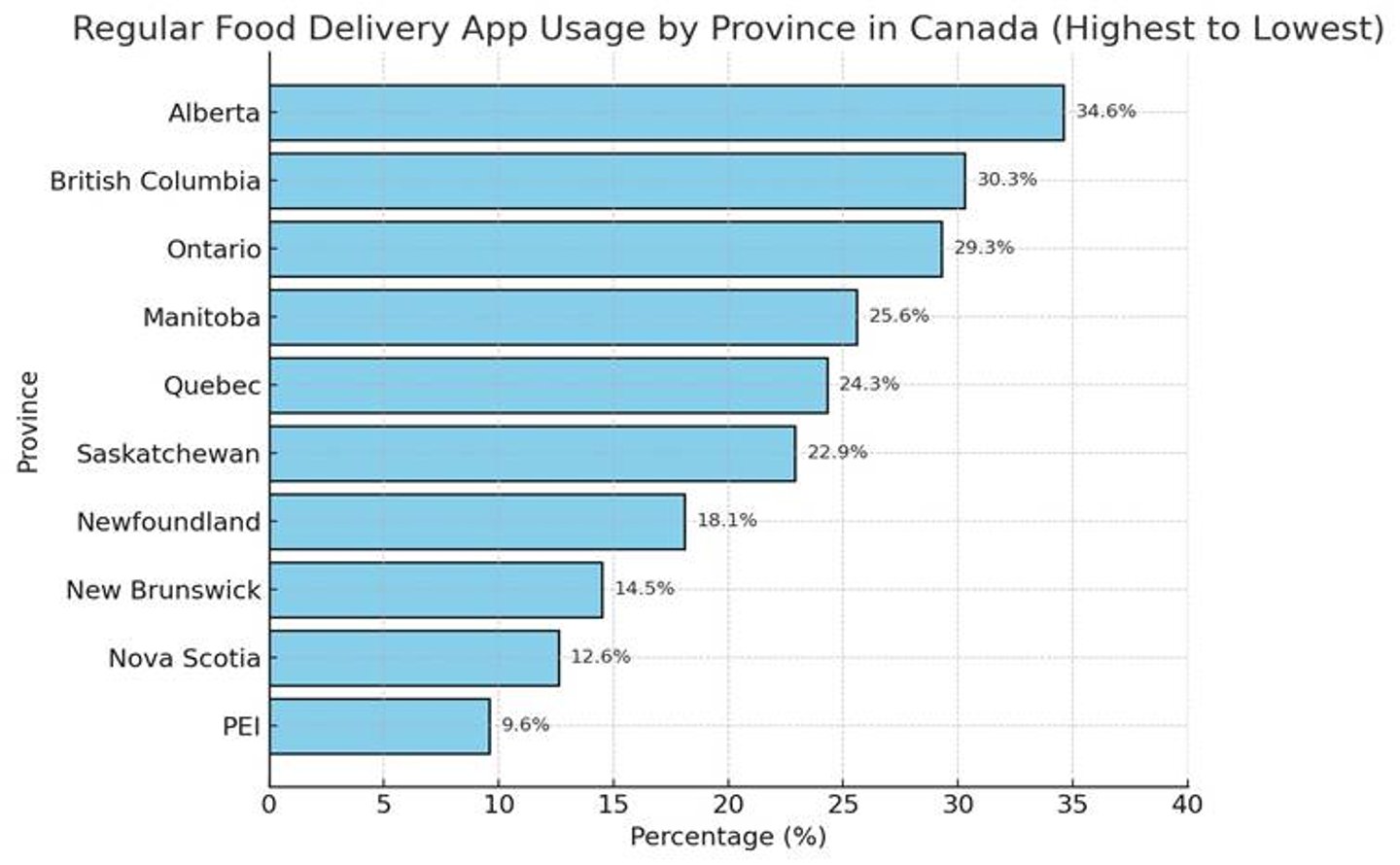

Regional differences are stark. Alberta leads the country with 34.6% of residents using delivery apps regularly, followed by British Columbia at 30.3%. Nationally, UberEats remains the reference platform, with nearly three-quarters (72.7%) of regular users.

But, adoption is far from universal. Nearly 58% of Canadians either stopped using these apps or never adopted them. Cost is the main deterrent: 57.2% point to food prices, while 52.9% cite platform fees. Here lies a paradox: while food inflation has pushed grocery baskets up by 27% over five years, food delivery services have gained ground. Canadians are showing a willingness to spend more not for the food itself, but to save time and increase convenience. Delivery, in this sense, is becoming a modern trade-off where efficiency and comfort outweigh strict economic rationality.

Generational patterns make this even clearer. Among millennials, 38.6% are regular users, closely followed by generation Z at 38.1%. By contrast, only 25.1% of generation X and 12.1% of baby boomers say they use these services regularly. Younger Canadians, despite having less disposable income, are more willing to allocate funds to delivery. For them, the smartphone is practically an organic extension of daily life. Ordering a meal with a few taps isn’t indulgence—it’s normalcy in a consumption culture shaped by instantaneity.

This has direct implications for the back-to-school season. College and university students—often living away from home for the first time, juggling coursework, part-time jobs and social lives—are especially drawn to food delivery apps. With limited cooking skills and tight schedules, many will turn to these services as an alternative to grocery shopping or campus dining halls. In fact, this demographic is likely to drive even higher seasonal spikes in usage, reinforcing how digital platforms are reshaping not just family kitchens, but also student life.

This trend, however, raises questions of food literacy. Older generations valued cooking and saw meals as moments of preparation and togetherness. Increasingly, younger Canadians outsource this step, with less time invested in the kitchen. The cultural shift carries consequences: it changes our relationship with food, weakens culinary skills, and may ultimately affect health and our connection to local food traditions.

Finally, it is important to remember that every delivered meal represents the work of farmers, processors, distributors and restaurateurs who uphold a complex and resilient food chain. As Canadians embrace convenience, we must not lose sight of this reality. Eating is never just consumption—it is a link to an entire national food economy. Recognizing that link, while adapting to new consumption models, is critical if we want to balance convenience with appreciation for the people and systems that put food on our tables.