Ottawa: Stop sending cheques to fight grocery prices. End the grocer blackout

Since Feb. 1 marks the end of the grocer blackout period, Metro’s CEO, Éric Laflèche, warned Canadians this week that food prices—particularly dry and pantry goods—would rise by more than 3% in many cases. On this point, he is right. Consumers should fully expect similar price increases from other major grocers since the blackout period applies across most of the industry.

The blackout period is an unwritten industry practice designed to help grocers manage the surge in transaction volumes during the holiday season. Retailers argue that operational constraints make price changes impractical during this time. As a result, suppliers are asked to freeze prices annually from Nov. 1 to Feb. 1. To consumers, the idea of a price freeze upstream may feel reassuring—but it shouldn’t.

In practice, this policy is economically counterproductive. Prices are routinely pushed up immediately before and after the blackout window, amplifying volatility and ultimately driving food prices higher over the year. Rather than stabilizing prices, the blackout period distorts them.

READ: How Canada became the food inflation capital of the G7

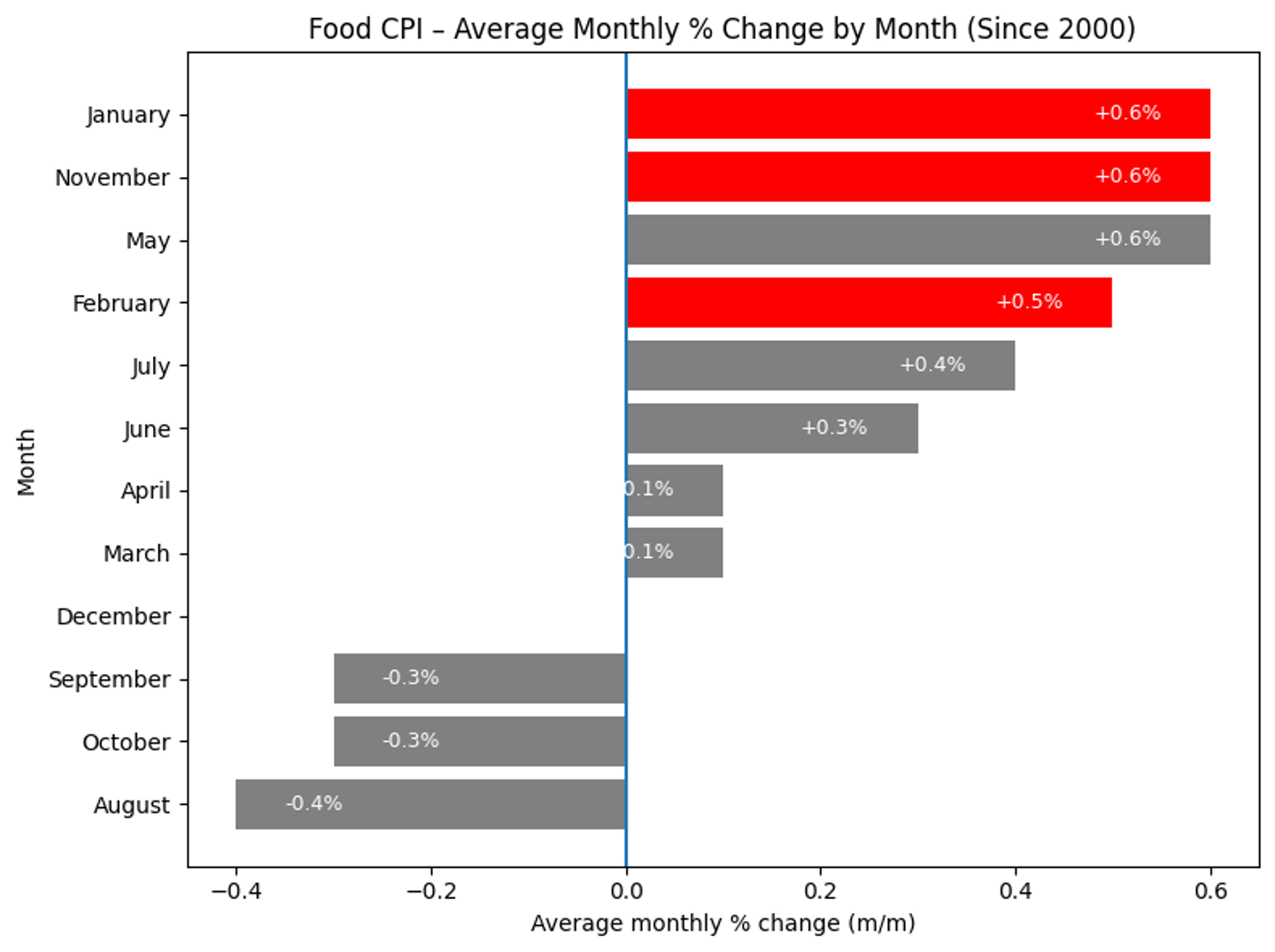

The data are revealing. Based on monthly food price changes observed since 2000—covering a 25-year period—three of the four months with the highest average one-month increases occur during the blackout window:

- January: ≈ +0.6%

- November: ≈ +0.6%

- May: ≈ +0.6%

- February: ≈ +0.5%

May is the only outlier. The broader pattern is clear: despite the supposed price freeze, food prices fluctuate more—not less—during the blackout period.

The economic logic is straightforward. When suppliers know that price adjustments will be prohibited for three months, increases are front-loaded in late October and again in early February. Across 25 years of data, this behaviour appears consistently, reinforcing the conclusion that the blackout period exacerbates, rather than dampens, price movements.

The blackout period is one of the most counterproductive practices in the food industry. It raises a legitimate question: how is this not a form of up-the-supply-chain coordination? Every year, major grocers simultaneously demand price freezes, yet retail prices continue to rise during the blackout—directly penalizing consumers.

This practice should end. Instead of relying on income-side measures like a bonified GST credit—at a cost of roughly $12 billion—a far more effective and cost-neutral step would be for Ottawa to ask grocers to abandon this flawed practice. Ending the blackout period would do more to reduce price volatility than many of the policies currently on the table.